Travel in Africa Up Close: Enormous opportunities for tourism but leadership?

It takes 17+ hours to fly the 7960 miles from to Johannesburg, South Africa from New York City. When the trip is made in coach class this is a decision that is not made casually. Under the best of circumstances, economy-level flying is challenging. When the time spent in a teeny tiny seat for almost a complete day, the opportunities for being uncomfortable expand geometrically.

Just looking at the coach class section of South African Airlines SAA (even without people), can trigger a panic attack. When filled with passengers and babies, personnel and food carts, the scene makes New Year’s Eve in Times Square look empty and quiet.

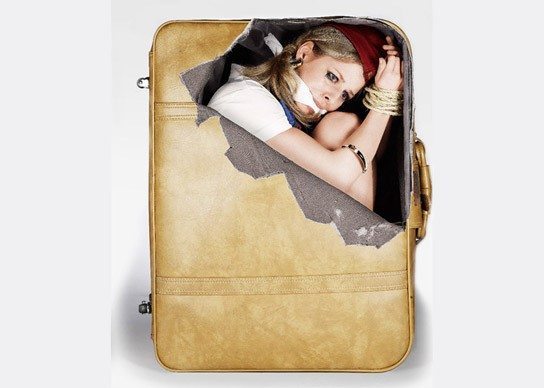

The good news for my outward bound trip was that the SAA flight was not completely sold out and I was able to expand across two seats and not feel like I was a body being compressed into a suitcase.

The bad news is that the remaining seats in the row were occupied by a man of giant proportions who thought that the entire row belonged to him, seizing the opportunity to occupy every seat in the aisle. Fortunately, I was able to reclaim my cherished space when I enlisted the aid of an airline staffer.

What to Know

Beyond the challenge of airline seating, travel throughout the African continent is not easy. Although the Mission of the African Union (55 African countries) is to promote a peaceful, prosperous and integrated Africa, little has been done to develop a strategic plan to implement the concept. Although the African Aspirations program for 2063 includes objectives for growth and sustainable development, political integration, and the support of Pan Africanism with a strong cultural identity and common heritage, progress is very slow.

It is not news that the growth of trade and tourism requires an efficient and effective infrastructure between countries. Unfortunately adequate land and sea connections (including roads, rails, and maritime) are currently unavailable. In some countries (i.e., Zimbabwe, South Africa), a few of the airports are starting to meet a demand for connectivity – but the modernization of all facilities is very slow.

It is also not news that border controls are chaotic, appear to be run by under-trained personnel who take their power of yes and no very seriously and frequently use their position to intimidate people seeking to travel from one country to another.

Visa costs vary from one country to another, with payments paid by a Canadian different from charges to an American. There appears to be little consistency in fee payment schedules, one country asks for a fee to enter while others want fees to enter and leave the country. Fee assessment(s) seem to be dependent upon the whims of the employees and not a set of established and fixed government-negotiated guidelines.

Another variable is the occupation of the visitor. People traveling on business or for leisure are treated differently and their visa fees suggest creativity rather than bureaucracy. Research through USA-based embassies and consulates prior to departure do not provide significantly accurate information, when/if guidelines are available at all.

Brand Africa

The exotic image of Africa is marred by poverty, strife, hunger, war, starvation, disease, and crime and a complex and disturbing infrastructure challenges travelers. Because perception is a reality the region self-limits many potential markets from visiting. While the public and private sectors should be working together to reconcile reality and perception with information that is current and accurate – an apparent acceptance of conditions (an ennui) is noted and accepted in both governmental and private sectors.

Looking for Leadership

Governments offer lip service regarding the importance of tourism development as an important economic engine. Speeches are written by African leaders calling for the national development of tourism as a mechanism to alleviate poverty, generate foreign revenue, and contribute to wildlife conservation; however, these leaders are not providing the resources necessary to develop a viable industry, leaving the growth entirely in the hands of private developers.

Currently, tourism revenues are generated through a narrow line of products such as wildlife and national parks based on a few species (i.e., the big five and the mountain gorillas). Leisure tourists are responsible for approximately 36 percent of the market and business travelers are responsible for 25 percent of international arrivals with 20 percent attributed to visiting friends and relatives. Other tourism categories include sports tourism, visits for medical treatments and attendance at meetings and conventions.

Leisure tourists with large budgets frequent Kenya, Seychelles, South Africa and Tanzania, while niche tourists participate in overland or cross-continental trips and adventures, cultural heritage, diving and bird watching tours. Lower-end tourists are likely to holiday in The Gambia, Kenya, and Senegal. Middle-income segments are missed because of marketing-errors – travelers perceive the cost of a tour to Sub-Saharan Africa as expensive in relation to its value.

To overcome the challenges facing the development and/or expansion of tourism executives will be forced to create an environment of political stability, enlightened governance, infrastructure development, consistent service standards, food /water safety, and personal security – all supported by an adequate budget and pro-active marketing and public relations programs.

Size Matters

The Tourism budgets for some African countries are very small. For example, Zimbabwe, with a National annual budget (2016) of $4.1 billion, allocated only $500,000 to tourism.

Very few countries are able to support tourism products without additional private sector resources. Kenya and Tanzania charge $40-$75 per day per person for park fees. The Rwanda Wildlife Authority charges visitors up to $750 per half day to track gorillas. Kenyans participate in tiered pricing systems with citizens and residents paying lower fees than foreign and international visitors.

Unfortunately, these fees are seldom sufficient to finance the multiple sustainability needs of parks, protected areas, and surrounding communities. Governments continuously search for add-on fees from minimally invasive businesses, and offer opportunities for tourists to contribute to the maintenance of the parks – but revenues generated are insufficient to cover costs.

Tourism Requires Planning

While South Africa is a popular hub, the nearby countries of Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Zambia offer interesting opportunities for unique travel experiences; hence, the first question is “Where do you want to go?”

Unless you have lived in Africa and/or know people who have lived or worked in this region, it is very difficult to determine where to go and how to get there. Unlike travel through the USA, Europe, Asia, the Caribbean and Mexico, it is not easy (and not recommended) to attempt a holiday in Africa without advance planning.

Tourism is recognized by the governments of the SADC countries as offering major opportunities for economic growth; however, Robert Cleverdon’s research (2001) finds that they have “allocated few developmental funds” to this endeavor. The SADC Coordinating Unit (tourism protocol) and Regional Tourism Organization of Southern Africa (RETOSA) (regional tourism marketing organization with a public-private sector marketing focus) have been formed and some countries have developed a dedicated Ministry of Tourism. A few other nations have implemented joint public-private sector tourism boards or councils; however, these institutions do not have the “technically qualified or experienced officials needed to guide, manage and monitor the development of a diverse sector like tourism,” and Cleverdon calls for the development of ongoing education and training programs that will develop groups of tourism professionals in each country. He also suggests that the countries “of the region… address the present failure to translate plan preparation into implementation” (Cleverdon, 2002).